Estrangement as the Beginning of True Praise

+ Estrangement in Literature: Kafka's Metamorphosis

Kafka’s “Metamorphosis” opens when Gregor—a hardworking young man living with his less-than-appreciative family has turned fully into a beetle. Fast forward a few scenes and he is scurrying along the walls of the apartment. The family has gone through pains to cover Gregor’s sudden and dramatic transformation and through a misunderstanding, Gregor is outside his bedroom and has been seen by a few visitors. His father is embarrassed and reaches for what’s in hand: apples.

The first apple: Gregor can dodge with little problem

The second apple: hits Gregor, but he is able to keep going

The third apple: lands into the soft center of his beetle back and stops him in his tracks. This apple—which no one will attempt to remove—will eventually be what kills Gregor.

Many people living in estrangement or within toxic family systems will recognize this pattern. Maybe we are surprised by the first blow, slowed by the second, but for some of us there comes to be a third (or three thousandth) that brings us to an impasse: we feel that we can no longer carry what has been thrown at us. I believe this is the moment where either our exoskeletons grow a little thicker or the doorway opens.

Before I became estranged from my biological family, I was sitting in my friend’s car, parked a little ways down the street but still within full view of my parent’s house. I was a few weeks sober and in many ways the whole world felt like I was looking at it through a giant microscope. I had not been fully awake in a very long time and that sensation brought some beautiful, but also terrifying prospects. As “The Metamorphosis” reveals itself we learn that Gregor has been supporting his family by over-working to relieve them of their debts. The family, while fully dependent on Gregor, has become resentful of him. And Gregor has told himself, “just a while longer.” He tapes the image of a beautiful woman to his walls and then denies himself any other existence than the one that has been prescribed to him. He works, he sleeps, he eats minimally, he pays what is owed. We might ask: wasn’t he already acting like a beetle before his physical transformation? I, too, had developed a system that allowed for a smallness—big enough to be resented, and hard enough to try to withstand the blows—to be a part of my family system. This is an indication of a self-estrangement. There is no relationship that can be healthy when it is predicated on the necessary shrinking of one party in order to function. My friend asked me to look out at the front yard, where my parents were throwing my possessions into the lawn and bushes. A voice was screaming out the window. An unleashed dog was chasing a feral cat. A neighbor had their face pressed into their window and was peering over, but that was only because she was new to the block. The other neighbors recognized this as just an ordinary day for my household. No one called for help. Like Gregor, I had been scurrying around the walls of this life dodging what I could. But something crystallized as I sat there with my friend. He asked, “do you think you could stay sober in this?”

I looked at him through the same microscope. At that point in my life, I had many outward losses, many of which I had initiated through my addiction. And while I had no questions about whether or not I was an addict, what I couldn’t believe yet was that there would be a world that was willing to support the sober version of myself. The one who was proving not to be as nimble to the things being thrown at her. The one who named pain, at least to herself, as it was happening. The one who looked at the exoskeleton she had formed within her family system and wondered if something could still be underneath.

In pieces of popular and personal media that center the stories of estrangement—often written by people without lived experience of it—I notice that the story of the day contact was broken is amplified. But that’s only the third apple.

Kafka had a terribly complicated relationship to his father, which he wrote about in “A Letter to My Father,” that, like many of Kafka’s works was published posthumously. The translators indicate that this letter may have never officially reached his father, but it’s left for us as a daring, circling, honest effort to confront an estranged family member.

The letter opens: “You asked me recently why I claim to be afraid of you. I did not know, as usual, how to answer, partly for the very reason that I am afraid of you, partly because an explanation of my fear would require more details than I could even begin to make coherent in speech.”

Kafka begins by acknowledging his father’s attempts at putting a story to their relationship, which of course, highlight the self-declared positive behaviors of the father. Kafka writes: “This, your usual analysis, I agree with only in so far as I also believe you to be entirely blameless for our estrangement. But I too am equally and utterly blameless. If I could bring you to acknowledge this, then - although a new life would not be possible, for that we are both much too old - there could yet be a sort of peace, not an end to your unrelenting reproaches, but at least a mitigation of them.”

To echo last week’s post, peace and amendment is a more practical, efficient, and possibly healing effort in an estrangement, which is markedly different from the efforts towards reconciliation that are often promoted.

One moment that I found truly striking in this letter is the way Kafka remembers how his father would encourage behaviors that were pleasing to the father and had little to nothing to do with Kafka’s identity or true nature:

“What I needed was a little encouragement, a little friendliness, a little help to keep my future open, instead you obstructed it, admittedly with the good intention of persuading me to go down a different path.But I was not fit for the path you chose. You encouraged me, for example, whenever I saluted or marched well, but I was no budding soldier, or you encouraged me when I could bring myself to eat heartily, especially when I drank beer, or when I managed to sing songs that I did not understand, or to parrot your own favourite cliches back to you, but none of it had a place in my future. And even today, it is typical of you only to encourage me in something when it engages your interest, when your own self-esteem is at stake, threatened either by me (for example with my marriage plans) or by others through me ….Then you give me encouragement, remind me of what I am worth, what sort of woman I could marry….But apart from the fact that I am, even at my present age, already virtually impervious to encouragement, I have to ask myself what good it could do me anyway, as it is only ever offered when I am not its primary object.”

It is hard to discern why we are encouraged when we live in environments that have us scavenging for acknowledgment of any kind. But this reflection kindled so many memories for me, especially at what it used to feel like to receive reward for being a “good beetle.” I told my friend, that day in his car, that I would not drink today, but I knew that I could not stay sober if I stayed. For me, using a substance is the same as dying and the need to leave immediately became crystallized under a new microscope.

For anyone currently dodging apples, who has left a dangerous system, or is considering what could be if they did: the only thing I’m certain of is that there is something radiant and true under our defense mechanisms. A light that persists and will be there waiting for you when you are ready to look.

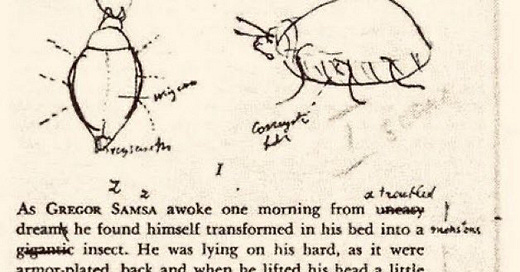

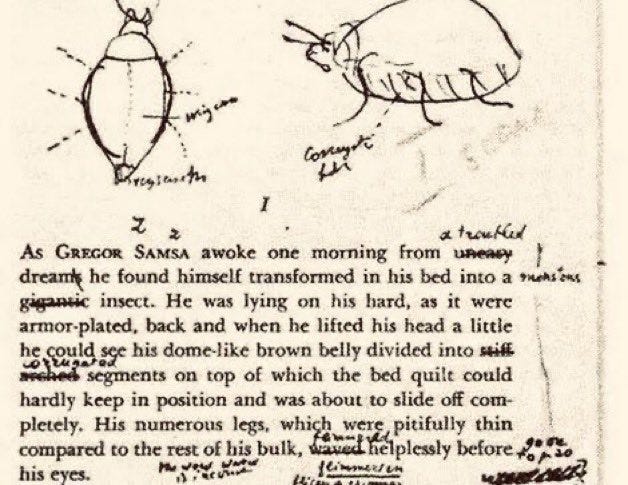

Image Credit: Nabokov’s annotated and illustrated “Metamorphosis”